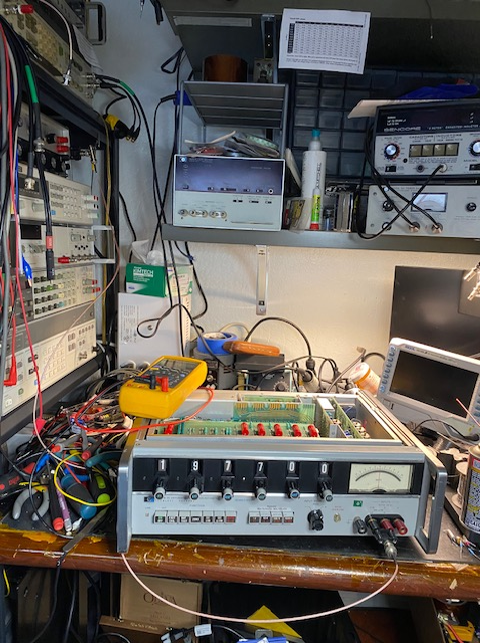

A little over a year ago I started hunting for the title of this article. It is as its name implies it is a DC voltmeter good down to about 20ppm. I’ll talk about it some after giving you some of the backstory. I’d been looking one to acquire for well over a year. A few months ago, I found one, bought it and promptly found out I got scammed. Got my money back though. A second stroke of better luck in November proved more productive. I located a 58-year-old example in Berlin Germany (viz a viz the Max Planck Institute) for a reasonable price. That’s not to say there were no hurdles. The seller didn’t want to ship to the USA. Bribing the man made him agree to shipping it. Once shipped it had to tediously wend its way through Germany, endure a flight to New York, languish for a couple of weeks in US Customs and then arduously make its way hence to the Oxnard Post Office folks who promptly intended to return it to the sender because they stated that the shipment was improperly addressed (BS; it was not). Fortunately, I was able to beat them to the bureaucratic punch and retrieve the delivery. Whew. Phase Two was hoping the sensitive instrument had not been damaged in shipment. Fortunately, it was not. After unboxing and after not forgetting to prudently switch the AC line voltage selector over to 115VAC from Germany’s 220VAC, I turned it on. No magic smoke… and nothing else either for that manner save one lonely neon power indicator and a pegged meter. Hmm. DOA as expected.

After much fuss and feathers, I was able to determine that the problem lay with the God-help-us dreaded HP photo-chopper circuit. What does that do? Well, as you know a DC signal cannot be readily amplified. So what HP did was to cleverly “chop” a DC signal into a square wave that can then be manipulated as an AC signal. HP used their photo chopper trick in a variety of their Test & Measurement products. Old school technology. These days it’s done with an IC or DAC. But back in the day it’s the best they could do. An example of the circa sixties photo chopper-based meter is HP 3400 RMS Voltmeter. I have several of these and cut my chopper expertise teeth with their finicky neon lamps. Believe it or not, many of these half century old remarkable meters are still in active use today. Looking for microvolts of power supply ripple? Need a high Crest Factor? Pull out the 3400.

Another photo chopper example is the HP 419A DC Null Voltmeter. I was lucky enough to acquire one. Lord knows I spent way too much time getting that little joker working and in spec. But I did. It runs on batteries or line voltage. I replaced the dead NiCads with LiiPro’s It’s a real current miser; a charge on the batteries lasts forever. It is exquisitely precise and sensitive and approaches what I consider to be a voltage measurement standard instrument. It’s so good it approaches the realm of spooky precise. If you can find one for sale that’s working, expect to lay out over a grand. If you’re really lucky, you just might find like I did, a DOA but fixable example at a far more reasonable price. Mr. Carlson of You Tube fame did a very interesting video on his 419A. The neon lamps in his instrument no longer worked right. Carlson pulled out some hair trying to source suitable replacements. He never did. He ended up devising a solid-state solution. I’m a purist. I stick with the original design.

Back to the 3420B; Being DOA certainly came as no surprise to me. After checking things out I ended up replacing a transistor on the board the generates the pulses that alternately “strike” the two neon lamps in the chopper. Thankfully, both the neon lamps were good.

Funny thing is that the transistor in question tested fine out of circuit but failed in circuit. The second clue came by looking at the transistor in circuit with a FLIR camara. It wasn’t hot and didn’t even feel warm to the touch, but looked a bit warm on the FLIR. Replacing it wasn’t easy either. Mainly because its proprietary part number is no longer extant. So I removed and determined its Hfe (beta) and matched it with a transistor I had on hand. Result? Well, a real sense of accomplishment accompanies turning off the lights and seeing the neon lamps dimly firing their characteristic soft orange hue. The meter works.

As luck would have it, I later found an exact NOS replacement and replaced the matched transistor. The instrument now functions to within about 50ppm. This after I replaced a few electrolytic caps that tested just fine because I’m there anyway. Like the 419A, the 3420B was designed to work from line voltage or NiCad batteries providing isolation from the line. The original 3420B batteries long since went the way of all flesh. I replaced them with four 2200uf electrolytic caps and few Zener diodes to regulate them at the intended rail voltages. If nothing else, they provide better filtering than the instrument being powered by the battery charging circuit alone. I think I can get it down to about 20ppm (0.002%) by doing a bit of delicate calibration. A complete calibration would require equipment I don’t have…. like a DC Transfer Standard and a Kevlin-Varley 100K divider. Sure, I could get a KV but I don’t relish laying out $3K for the privilege. Such being the case, as of this writing I’m waiting for some precision resistors to show up for the purpose of constructing a divider that should prove adequate for making some slight but meaningful decade selector tweaks that I hope will improve accuracy. If you want to see the HP3420B in action, just do a search on You tube for “HP 3420B”. A kindly gentleman by the name of George Ramsey posted an enjoyable video featuring a 3420B that he acquired and restored.

Some would say I’m wasting my retirement time, others that I’m just crazy and geeked out. But I enjoy restoring a neglected beautifully engineered vintage instrument. If it doesn’t work, it becomes a battle of wits… a chess game, my mind against a damnably obstinate inanimate instrument. All it takes is patience and perseverance… plus a bit of luck and some well-considered SWAG to triumph over repeated failures. And in the end, I gain yet another treasured shelf queen that may or may not be called into future service. More importantly, enduring a trying experience is the price of experience. What was difficult this time might not prove be so terrible next time. But don’t count on it. Clem-KM6OKZ